First published at Vlad Tepes. KGS

Fjordman: A Brief History of Pasta

In recent weeks I’ve been on two major travels, one to Beijing, China, and another to northern Italy. I couldn’t really afford to go, but then I got some money from the CIA and the Mossad for my Islamophobic essays. I also remembered that I had not cashed in on my annual white privilege bonus for a few years. Once I had done that, I could go for a holiday, anyway.

I will describe my impressions from these travels in later essays, but will start with reflecting on the history of pasta. I talked to one Italian man who believed that pasta was invented by the Arabs, whereas another frequent claim is that it was invented by the Chinese. I am personally skeptical of both these claims. To quote food historian Linda Civitello in Cuisine and Culture:

“For hundreds of years, it was accepted ‘fact’ that Marco Polo discovered noodles in China and brought them back to Europe. Now, in his masterwork, A Mediterranean Feast, food historian Clifford Wright states flatly that there is no truth to the story of Polo and pasta. Wright unravels the tangled strands of the origin of pasta and takes it down to its basic ingredient: hard semolina or durum (Latin for ‘hard’) wheat. This makes pasta different from bread, which is made from soft wheat. The Chinese did not have durum wheat. Wright places the origins of ‘true macaroni’ – pasta made from durum wheat and dried, which gives it a long shelf life – ‘at the juncture of medieval Sicilian, Italian and Arab cultures.’”

Marco Polo (1254-1324) was the son of a merchant from Venice in northern Italy who had good contacts in the East. The book Il Milione (“The Million”), describing his alleged travels in Asia in the late thirteenth century, became hugely popular in the Renaissance period and inspired other European travelers in their search for Asia, among them Christopher Columbus. Polo supposedly spent years in Mongol-ruled China but never mentions tea, nor the Great Wall or the practice of foot binding, which crippled millions of Chinese women well into the twentieth century. It is quite possible that he was a well-traveled man for his time, but scholars are still arguing about whether he really did all of the things he claimed to have done.

Marco Polo (1254-1324) was the son of a merchant from Venice in northern Italy who had good contacts in the East. The book Il Milione (“The Million”), describing his alleged travels in Asia in the late thirteenth century, became hugely popular in the Renaissance period and inspired other European travelers in their search for Asia, among them Christopher Columbus. Polo supposedly spent years in Mongol-ruled China but never mentions tea, nor the Great Wall or the practice of foot binding, which crippled millions of Chinese women well into the twentieth century. It is quite possible that he was a well-traveled man for his time, but scholars are still arguing about whether he really did all of the things he claimed to have done.

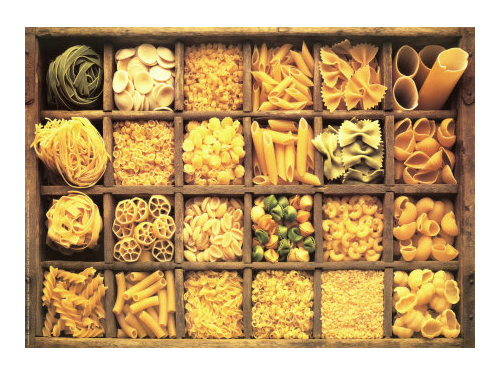

Noodles or noodle-like foods made of wheat, buckwheat, rice or soya have been enjoyed in China, Korea and Japan for a very long time and we have no indications that pasta existed in the Roman Empire, but these foods do not taste alike and are made from different materials and methods. Besides, pasta is a lot more than spaghetti, and many varieties do not resemble noodles even superficially. There is no strong historical or logical reason to assume that the inventions of East Asian noodles and Italian pasta were directly connected. Pasta from durum wheat was an innovation of the European Middle Ages. Middle Easterners before and after the rise of Islam used durum wheat, but Muslims apparently never invented pasta-like foods.

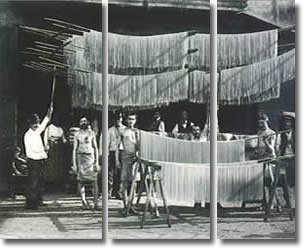

Historian Toussaint-Samat, too, questions the myth that it was imported to Italy with Polo. Anything resembling modern pasta cannot be traced with certainty much further back than to southern Italy in the thirteenth or fourteenth centuries AD. If you believe A History of Food, “the first production of pasta on any kind of industrial scale was indeed in Naples in the early fifteenth century. However, this pasta did not keep well, and it was not until 1800 that the process which would make it really asciutta (dry) was discovered. It involved natural drying alternately in hot and cold temperatures. Perfect conditions were found at Torre Annunziata, some kilometres south of Naples itself, where the climate changes four times a day, to a regular pattern. The macaroni of Torre Annunziata is the ne plus ultra of Italian pasta.”

The great merit of pasta, and one of the secrets behind its tremendous international success in recent years, is that it is very easy to make and also takes up little storage space, but swells when cooked. Cooking it is simple, too, since it only requires a large pot filled with water.

Another food myth is that Marco Polo introduced ice cream to Italy and Europe from China. Frozen desserts made from fruits or berries combined with ice and snow brought down from nearby mountaintops were served in several ancient civilizations, including ancient Rome. Whether this constituted ice cream as we think of it is debatable, however. A more recognizable version appeared in Renaissance banquets, with modern European ice cream dating back to the 1500s and 1600s. And yes, Italians did play a major role in this story.

I am personally a fan of Chinese cuisine, as are millions of other non-Chinese around the world judged by the popularity of Chinese restaurants, but I have to say that their dinners and warm dishes are a lot better than their sweets and desserts. I brought back some alleged Chinese sweets and candies to Europe and literally couldn’t give them away for free to my youngest relatives. It is the first time I have experienced children saying no to candy. There is nothing made in China, at least not today, that can be remotely confused with Italian gelato.

I am personally a fan of Chinese cuisine, as are millions of other non-Chinese around the world judged by the popularity of Chinese restaurants, but I have to say that their dinners and warm dishes are a lot better than their sweets and desserts. I brought back some alleged Chinese sweets and candies to Europe and literally couldn’t give them away for free to my youngest relatives. It is the first time I have experienced children saying no to candy. There is nothing made in China, at least not today, that can be remotely confused with Italian gelato.

Gelato is Italy’s unique version of ice cream, but with significantly less butterfat and higher sugar content than regular ice cream. It is less solidly frozen, melts in the mouth faster, has a richer, creamier taste and is denser because not as much air is whipped into the mixture. It is extremely delicious, and to Western tastes easily beats anything similar produced in China.